Ernst Abrele arrived in Norway with his wife Gertrud in 1939, and settled in Lillehammer.

From: Aberle, Ernst and Møller, Arvid. 1980. Introduction to: ”Vi må ikke glemme” – (We must not forget). Oslo: Cappelen.

Translated from Norwgian: Ingvild BeggWhen I now present my own story and the history of my faith, it is to tell the young ones what racism and dictatorship may lead to and are still leading to.

Threat of divorce

Soon after I was arrested at Lillehammer the police again arrived at our door to collect my cloths. At the same time they demanded Gertrud's cloths and her wedding ring. Gertrud protested energetically and told them that they might as well arrest her, as she could not walk naked through Lillehammer's streets. This action later turned out to be a cooperation between Lillehammer's notorious Head of Gestapo and a very energetic lawyer from Hamar. Twice Gertrud was called in for interrogation. What the Gestapo tried to achieve was to make her apply for a divorce from me. She refused point blank. (She was also in a letter told to return to Germany on a given date. She was put into hospital for 4 weeks by friends and pretended not to have got the letter. Then she got the second letter, but as Aberle and she had no citizenship she was allowed to stay. Friends in Lillehammer helped her)I remember everything which happened between 26th and 27th November 1942. The time is 3. Between low gray barracks 360 men stand in a row in the darkness of November. One or two of theme are 17-year old and one or two very old. Most of them are between 20 and 70. Some in dark suits, others in plus-fours and knitted cardigans, dressed as they were when they were arrested 4 weeks previously, just before sunrise on 26th October. One thing did they have in common. They were Jews, living in Norway.

The black car of the Commandant drew up on the place of the roll call (apellplass) with the lights on. A table is placed in front of the car. Chief Lindseth takes a piece of paper from his bag. He reads the name of all 360 prisoners. My name is the very first one, coming through the darkness.

Are you married? he shouts.

Yes, I answer

With a Jew or an Arian?

My wife is not a Jew!

Those who are not married step to the right. Those married to Jewish

wives also step to the right.

The Chief flips his papers, confers with the Commandant.

Those who are married to non-Jews step to the left. Quick!

Half hundred men to the left and more than 300 to the right.

You who stand to the right: March on!

300 pair of shoes against wet November soil.

You who stand to the left, back to the barracks. Quick!

There was no time for farewells between fathers and sons, between brothers, between friends.

In the barracks the rumours were rife in the early hours of the morning. We, the half hundred, married to non-Jewish wives, should be set free. The others were to be moved to another camp further into the country.

So were the rumours.

The prisoners who were married to what the Germans called Arian women were marched down to Berg train station that night. When darkness turned to day, the train left.

Grini, a day in August 1943

I got there in June, while most of the previous German citizens were transferred as early as March. This day I was doing agricultural work. I was the only Jew allowed to do this. We were 5 in each team. A well mature soldier from Sachsen was the guard. All the guards came from this area of Germany. None of them were fit for fighting. The guard approached me and started talking. I realised that he was pleased to meet someone who could speak his own mother tongue. Suddenly he pointed at my Jewish star on my lapel.

Is this a war distinction then? He asked.

Surly you know this is the Jewish star, said I, looking up from

work.

Jewish star?

He looked around and whispered:

I came here from Warsaw. There I saw several of your people being arrested and gassed to death. Others have told me about similar things in other places. I really thought there were no living Jews left any longer.

I stood as paralysed.

The guard from Sachsen moved on, stopped by another prisoner, asked him to work faster.

It cannot be true, I said to myself. It has to be a rumour. I will not tell my fellow prisoners. Everything he said are just rumours to frighten, rumours set out to get the Jewish prisoners to obey the least order. It cannot be true.

I am…

I am Ernst Aberle, born 18th May 1898 in Berlin, as the third son of my parents, Jacob and Clara Aberle, maiden name Lipmann. The Aberle family comes from Mannheim and the family tree goes back to 1700. The family name of Aberle was given to my great great grandfather during the time of Napoleon, when all citizens were obliged to choose a name. My great great grandfather was an art and furniture dealer in Mannheim and was "Hofjude" with the Duke of Baden.

On my mother's side we can follow the family back to Rabbi Simon Spiro, who lived from 1600 to 1679 in Prague and who for 40 years was Chief Rabbi of Böhmen. As Chief Rabbi he also took part in the defence of Prague against the Swedes in 1648, when the Jewish congregation received thanks and accolades from the Emperor Ferdinand the third of Austria for their courage during the Swedish siege.

Nobody on our side of the family has been particularly interested in family research, but a printed family tree existed where I had found all this information. In the oldest Jewish cemetery in Europe - in Prague - my forefathers' graves can be found. In Prague there is also a monument for one of my forefathers on my mother's side. It is the Portheim Palace, which is a pearl of construction art, in the baroque style. It was Leopold Juda Porges, born 1785 and died in 1869, who owned the palace. He was the founder of the Austrian cotton industry and the first using steam power. He was made a peer and was from 1841 called Edler von Portheim. He was my great great grandfather and he was the same for Professor Victor Goldschmidt from Oslo, one of the best known geologists of our time. Fate and the family history assisted him in helping me to come to Norway in 1939. In other words you can not just dismiss the usefulness of knowing a bit of your family history. When this has been mentioned it is also because it can throw some light over some part of my further destiny. But I will return to this.

Bülowstrasse, Kleiststrasse and Uhlandstrasse

My childhood was happy and harmonic. I mentioned that I was the third born. 11 years after I was born we got a sister, but the age difference and the experiences during the war gave us boys a much closer relationship

I grew up in Bülowstrasse and Kleiststrasse. My father had a printing business with 180 employees in the east part of Berlin. The Berlin I experienced during my boyhood was a changing Berlin. When I was 6-7 year old, the building of the Underground started. In our house we got a lift installed and hot and cold water.

(He was much younger than his brothers and was called Ceberle. The first born was Aberle and the second Beberle.)

I was never quite comfortable at school. It was as if the system did not suit me. The breaks were the best. Then we played together with other boys, both Jewish and boys from other families. The only difference between us was the religious teaching. Then the children from Jewish families were separated from the others. But we never heard any harsh word, and never did we suffer for being Jews.

The Front is calling

In 1914 I was 16 years old. I had finished the first year at high school in Berlin.

Every evening thousands of youngsters gathered at the Kurfürstendamm. The enthusiasm was great. The latest news from the front was told, the joy was immense over the 'perfidious' English at last would be paying the penalty. When I came home one evening and told my father about the hate of the English among the Berliners he just said: - "Don't worry about that Ernst. I have actually lived in England for so many years that I know the British as far from 'perfidious'."

(His two brothers volunteered to the army. In 1916 he was enlisted and took part in the war, and was wounded.)

On the Front we Jews fought side by side with the non-Jews. When the war came close to the end I noticed for the first time that Jews were not so popular in certain areas, especially among academics and officers. Hans, my older brother fought at the Front for 34 long months. At home all were surprised that he had not been promoted to officer. When Hans returned he told us that the head of the regiment did not want Jews for officers.

As early as in January 1919 came the threat against the government of Ebert through the Spartacists, led by Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg. The Old Front warriors were asked for volunteers. This time and twice later I did. Later it turned out that this call was the start of an anti-republican movement and it gathered a lot of future nazies. In the world the Jews were slowly starting to become the political shuttlecocks.

Schutz- und Trutzbund and rubber battons

The first serious understanding of what it meant to be a Jew I got in 1920.

The summer of 1921 I met Gertrud. (She was a nurse and from Berlin.)

…I passed my Diploma exam in November 1922. The same year I was employed by a firm in Berlin making machines. Unemployment was rife all over and during 7 years I changed my place of work five times. I was lucky. I was only unemployed for four weeks.

The net tightens

In November 1929 I became unemployed. For four weeks I was without work. Then my firm in Berlin got a rationalisation job in Brno in Czechoslovakia, and I ended up agreeing to travel to the biggest city in Moravia, a beautiful city with a quarter million inhabitants.

After two years the trouble started. My work permit in Czechoslovakia was originally valid for 2 years, I got another year, but then I was refused a further extension. By this time the political situation in my own country had become so difficult that I had no wish to return. It was clear to everybody that Jews were no longer accepted like other Germans. Luckily enough I got a trading permit in Czechoslovakia. With some difficulties my permit to stay was extended.

Then the occupation of Austria took place. I had worked as a consultant at an enamel factory in Knittelfeldt. I knew that most Austrian feared Adolf Hitler. But I also knew that some of them had no fear of him. After all, he is one of our own, people in the countryside said - one who is himself an Austrian would never do anything wrong against his own people.

I remember a St. Hans party in Knittelfeldt. It was the Gym Association that arranged the party. When the bon fire was lit, Gertrud and I left the party. The bon fire was formed as a swastika. The year was 1936. (page 29)

The spring of 1938 the Austrian with the black moustache marched into his fatherland. We then realise that we were in a difficult position.

If he can manage to enter Austria that easy, anything can happen, said Gertrud.

(His sister went to USA and one brother went to South Africa. The other brother died in 1920, aged 25 years)

My cousin was arrested on the Crystal Night. In January 1939 he returned back to Berlin after being at the concentration camp in Sachsenhausen. He wrote me as letter:"It is about time you look for something else too, Ernest," he wrote.

Then I realised that it was a question about to be or not to be. To live or die. But now nobody wanted to accept Jews. We got the feeling of being completely isolated from the rest of the word. My mother was allowed to leave Germany just a week before the Crystal Night. The only reason she was allowed to leave was that she had a son in South Africa that she wanted to visit.

From the USA we had received an affidavit through relatives who had lived there for several years. On this basis we applied for visa at the American Consulate. After several months of intense waiting we were told that at the best we would have to wait another six months. But on October 1938 the Germans occupied the Sudentenland and that meant that the quota system automatically was amalgamated with the German quota. This meant that the waiting time became two years rather than six months.

What we then knew was that the only possibility for people with German passports was to travel either to Shanghai in China or to Finland. The spaces on board the ships to Shanghai were booked two years forward in time. A friend in Brno said that the possibilities of getting to Finland were not much better. To go there you had to travel through Poland in sealed railway carriages. When the train arrived at the border the people on board were merely asked if they minded returning to Germany. And then they were sent back where they came from.

(He tried for Shanghai but then) The same day I visited a good old friend in Prague. He told me that he had just returned from a business trip in Scandinavia. He had been told that there was a Norwegian delegation in Czechoslovakia with the task of finding 100 Labour Union members among the Sudentenland Germans. The idea was that those 100 should come to Norway.

I knew well the work Fridtjof Nansen had done for refugees in many countries. Therefore I decided to do everything in my power to talk with his son Odd Nansen who turned out to be a member of the Norwegian delegation in Prague.

(He met Odd Nansen and his wife) "I will do everything in my power to get you and your wife out of Czechoslovakia and into Norway," was the last thing he said. I returned happily to Brno.

After some weeks of intense waiting came the letter from the central Pass Office. Visa has been refused, was all it said. All hope seemed to have gone. But in the same envelope was a letter from Nansen. We did not accept this decision and therefore his assistant had approached the Department of Justice that day. "You will hear as soon as we get a response from the Ministry" he wrote.

Weeks and months went without a word. But then, one day a letter came from the Norwegian Consulate in Prague. We had then reached October 1939. Entry into Norway for Gertrud and Ernest Aberle had been approved, was the short message. Permission to stay will last until the visa for the USA would come through.

(They left 10th November)

We had to leave Czechoslovakia in order to survive. However, we had more sympathy for the Czechs and their country than for our own fatherland and our own countrymen, the Germans.

(They were then without Citizenship when they came to Lillehammer. He got work at the Uldvaren factory. But after the war he was sent from the prisoner of war camp to Sweden on 1st May 1945, and was allowed back to Norway only in July 1945, after a lot of political wrangling because he was without citizenship. However, he had good people fighting for him and his wife in Norway)

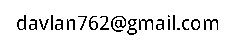

Top left: "Two young Berlinners who later became a couple. Gertrud photographed in 1918, I as a young student two years previously" Bottom: "Gertrud and I photographed in our flat in Lillehammer some years ago. Now I am here on my own ..."

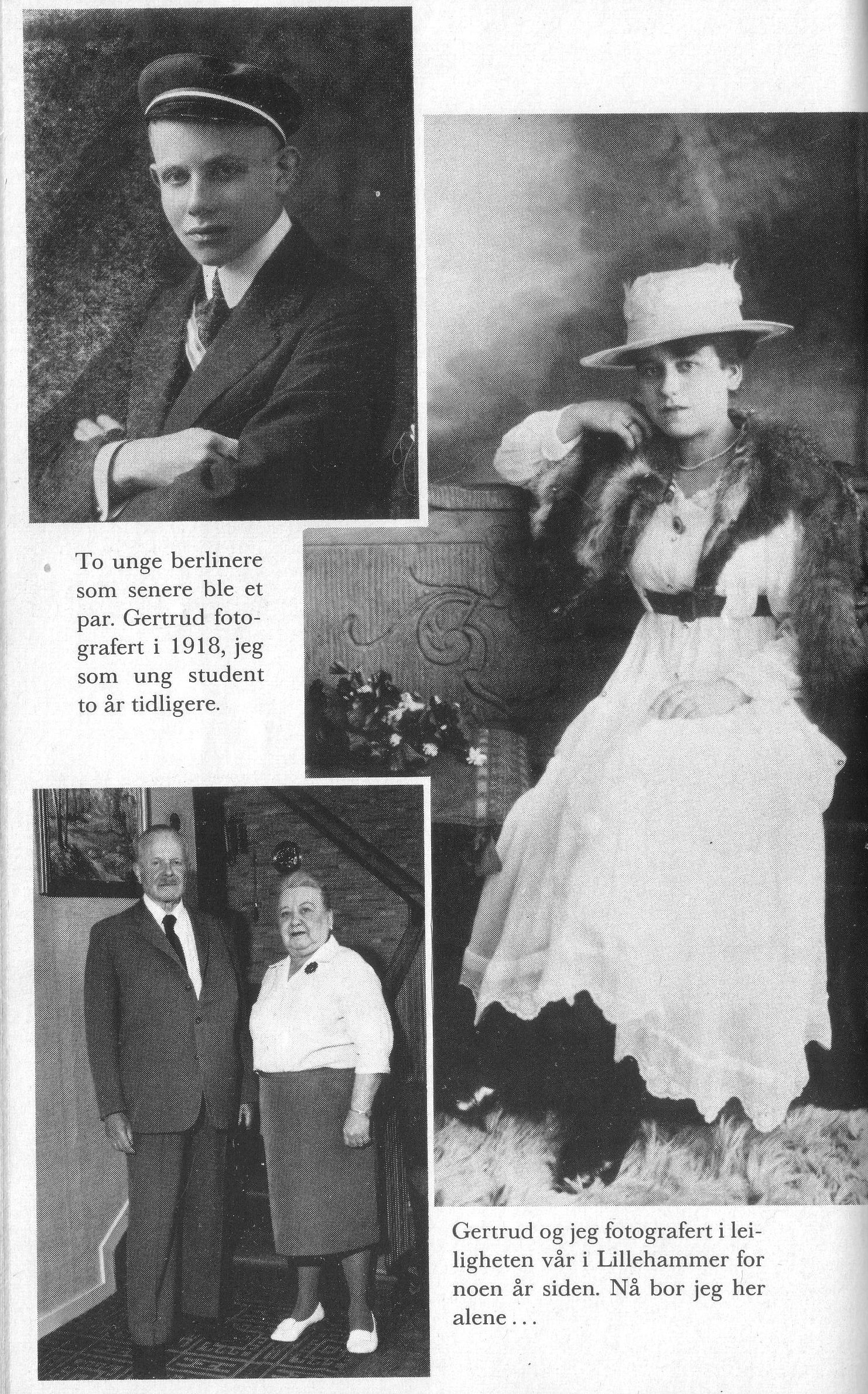

Here I am to the far right in the trenches at Illyxt in June 1917, a month before I was wounded.

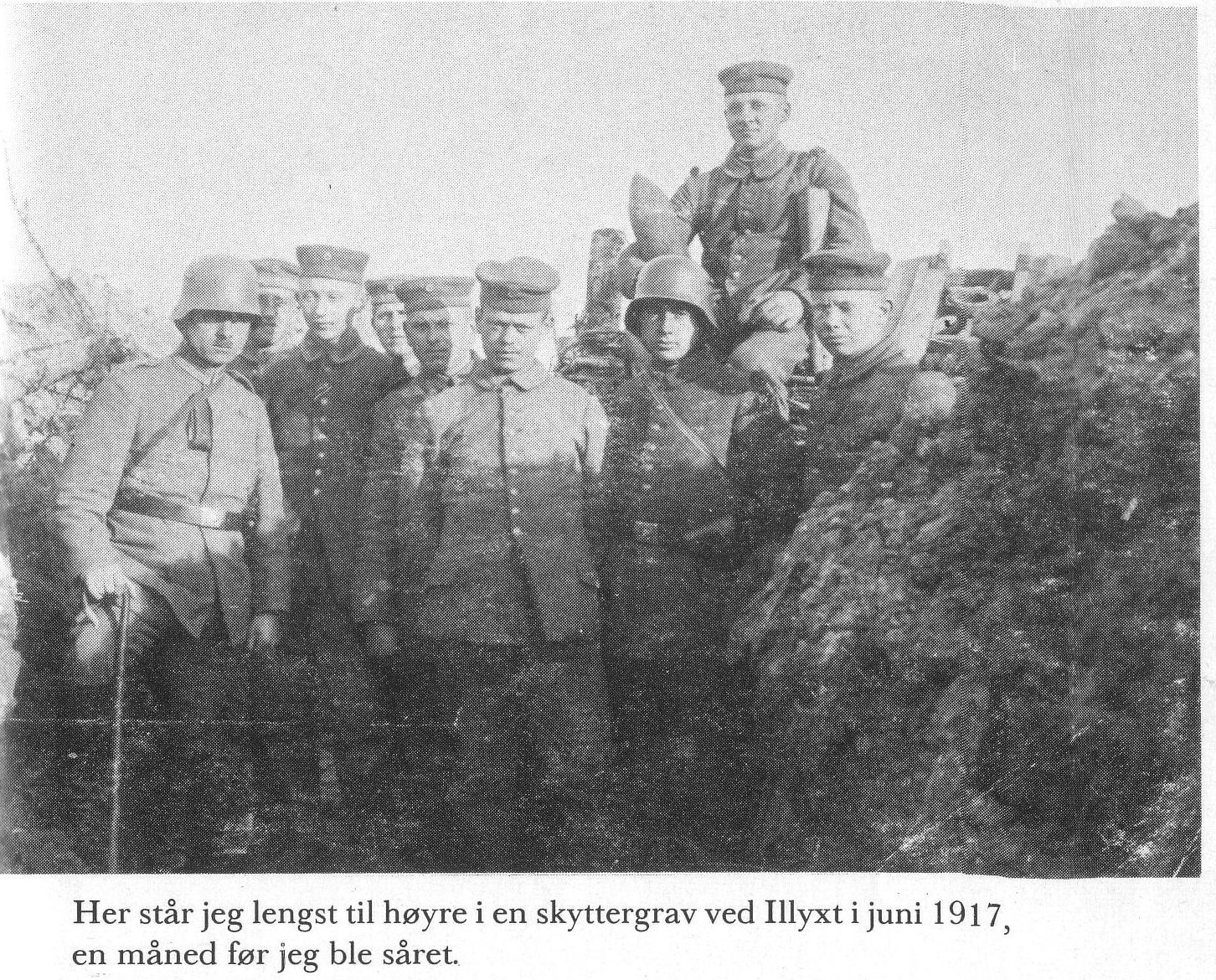

This picture is taken in the garrison at Arys. I am standing to the far right together with my soldier friends.

From: Abrahamson, Samuel. 1983. The Holocaust in Norway. In: Contempory Views of the Holocaust. Ed. Braham, Randolph L., pp. 109-142. The Hague: Kluwer Nijhoff Publishing.

None of the Scandinavian Jewish communities suffered such staggering losses during World War II as did the Jews of Norway. Forty-nine percent of her Jewish population was murdered, a percentage higher than that of France (26 percent) Bulgaria (22 percent) or Italy (20 percent). (p. 109)

Having suffered defeats in the attempted nazification of Norway's organized associations, legal and sports organizations, labor unions, teacher and student groups, churches, and civil servants' unions, Quislings and the Nazi leaders turned their undivided attention towards a defenseless group – the Jewish communities in Norway. (p. 118)

The arrested Jews were transported first to Bredtvedt, a detention camp outside of Oslo, and then to Berg cocentration camp near Tønsberg. Ernst Aberle, a refugee from Czechoslovakia arrested in his home at Lillehammer (about 150 miles north of Oslo), gave a detailed description of those events. He recounts that the Berg camp was under Norwegian administration, with Major Eivind Wallestad and Lieutenant Leif Lindseth in command. The camp was totally unfit for human habitation. There was no water and no toilet facilities at all. (p. 127)

“Exception are made for women and men married to persons not having J in their passports, ...” About 55 persons of mixed marriages were interned in Norway until May 1945, at which time they were safely moved to Sweden. (p. 129)

Last updated: November 25, 2014